7 PLOTS

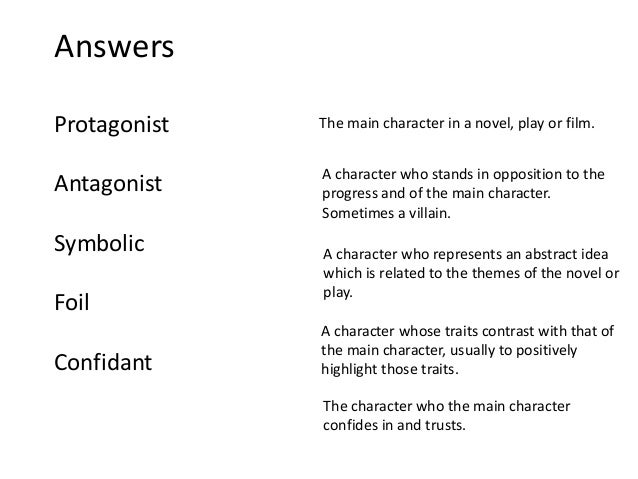

Types based on role include:

- Protagonist

- Antagonist

- Deuteragonist-

Deuteragonist

Most stories have a primary protagonist and a secondary deuteragonist (or group of deuteragonists). This is the character who’s not exactly in the spotlight, but pretty close to it.DR WATSON - Tertiary

Tertiary characters

The reason that tertiary characters aren’t called “tertagonists” is because they’re not important enough to really agonize anything or anyone. They flit in and out of the MC’s life, perhaps only appearing in one or two scenes throughout the book.- Padma and Parvati Patil in Harry Potter

- Confidante

- Love interest

- Foil

Types based on quality include:

- Dynamic/changing

- Static/unchanging

- Stock

- Symbolic

- Round

12 Types of Characters Featured in Almost All Stories

They say it takes all kinds to make the world go round — and the same is true of stories. Whether you’re writing fantasy, romance, or action-adventure, you’re going to need certain types of characters to keep the plot moving and your readers intrigued!

That’s why we’ve put together this handy-dandy guide of 12 character types featured in almost every story: to help you figure out which ones you need, how they relate to one another, and what purposes they can serve.

What are the different types of characters?

Most writers have an inherent understanding of how to categorize their characters based on classic, “comic book-style” labels: heroes, villains, sidekicks, etc. But in the ever-intricate realm of stories, there are many more nuanced types to consider!

Before we explore these types, however, you should know that there are two main ways to classify them: by role, and by quality.

Role

Character role refers to the part that one plays in the story. As you probably know, the most important role in any story is the protagonist (which we’ll discuss below). This means all other roles stem from their relationship to the protagonist. Basically, these types define how characters interact and affect one another.

Types based on role include:

- Protagonist

- Antagonist

- Deuteragonist

- Tertiary

- Confidante

- Love interest

- Foil

Some of these roles can overlap. A deuteragonist might be the MC’s confidante. The antagonist might be their foil. Or the antagonist might eventually become the protagonist’s love interest! (Any fans of the enemies-to-lovers trope up in here?)

But we’re getting ahead of ourselves. Let’s quickly touch on the second major category of character types.

Quality

Character quality has to do with what kind of character someone is. This doesn’t refer to their temperament, such as being nice or mean, but rather their nature within the story, such as being dynamic or static.

These types tend to define narrative purpose in a story. For example, a dynamic figure creates a compelling arc for readers to follow, and a symbolic one represents some underlying theme or moral.

Types based on quality include:

- Dynamic/changing

- Static/unchanging

- Stock

- Symbolic

- Round

These may also overlap, though less so than the roles. You’ll see how as we discuss them below! Without further ado, let’s dive into the various types of characters listed here.

Character Types by Role

1. Protagonist

The protagonist is likely a pretty familiar concept for most of us: this is the main character, the big cheese, the star of the show. Most of the action centers around them, and they’re the one we’re meant to care about the most.

In stories written with a first-person point of view, the protagonist is usually the narrator, but not always. The narrator can also be someone close to the MC (like Nick in The Great Gatsby), or e someone completely removed (though this is relatively rare).

Every single story has to have a protagonist, no matter what. Simply put, no protagonist = no plot. Remember, all other roles are defined in relation to the protagonist — so if you’re currently planning a story, this should be the very first character you flesh out.

Protagonist examples: Harry Potter, Frodo Baggins, Katniss Everdeen, John McClane, Dorothy Gale, Hercule Poirot, Indiana Jones, Walter White (who is actually an anti-hero, as opposed to the traditional hero).

Indiana Jones — a classic protag if there ever was one. Image: Paramount Pictures

2. Antagonist

If you’re an antagonist, you antagonize — it’s what you do. Specifically, you undermine, thwart, battle, or otherwise oppose one character: the protagonist.

Most of the time, the protagonist is good and the antagonist is evil, and such is the source of their conflict. This isn’t always the case — especially if the protagonist is an anti-hero who lacks typical heroic attributes, or the antagonist is an anti-villain who has noble characteristics. Still, 95% of the time, the protag is the hero and the “antag” is the villain.

Antagonists usually play just as important a role in a story as their protagonistic counterparts, but they may not be seen as much. They tend not to narrate stories and often operate in secret. Indeed, the question of “What will the antagonist do next?” can be a source of great narrative tension in a story.

Antagonist examples: Sauron, Voldemort, The White Witch, Count Olaf, Maleficent, Iago, Regina George

3. Deuteragonist

Most stories have a primary protagonist and a secondary deuteragonist (or group of deuteragonists). This is the character who’s not exactly in the spotlight, but pretty close to it.

The deuteragonist’s “comic book” equivalent would probably be the sidekick. They’re often seen in the company of the protagonist — giving advice, plotting against their rivals, and generally lending a helping hand. Their presence and close relationship to the protagonist gives the story warmth and heart, so it’s not just about the hero’s journey, but about the friends they make along the way (awww). Of course, not all secondary figures are friends — some are arch-enemies — but even these less-friendly deuteragonists still lend depth to a story.

Deuteragonist examples: Ron and Hermione, Samwise Gamgee, Lumiere and Cogsworth, Jane Bennet, Dr. Watson, Mercutio

4. Tertiary characters

The reason that tertiary characters aren’t called “tertagonists” is because they’re not important enough to really agonize anything or anyone. They flit in and out of the MC’s life, perhaps only appearing in one or two scenes throughout the book.

However, a well-rounded story still requires a few tertiaries. We all have them in real life, after all — the barista you only see once a week, the random guy you sit next to in class — so any realistic fictional story should include them too.

In the following list of examples, we’ve put the sources of these tertiary characters in addition to their names, just in case you don’t recognize them. (We certainly couldn’t blame you.)

Tertiary examples: Mr. Poe in A Series of Unfortunate Events, Radagast in The Lord of the Rings, Padma and Parvati Patil in Harry Potter, Calo and Fabrizio in The Godfather, Madame Stahl in Anna Karenina

Who the heck is this guy? Doesn't really matter, he's tertiary. Image: Warner Bros.

5. Love interest

Most novels contain romance in one form or another. It might be the main plot, a subplot, or just a blip on the narrative radar — but no matter how it features, there has to be some sort of love interest involved. This love interest is typically a deuteragonist, but not exclusively (hence why this separate category).

You’ll recognize a love interest by the protagonist’s strong reaction to them, though that reaction can vary widely. Some love interests make their MC swoon; others make them scoff. The protagonist often denies their feelings for this person at first, or vice-versa, which is a great plot-thickening device.

No matter what, if they’re well-written, you should find yourself curious about (if not always rooting for) whatever love interest pops up on the page.

Love interest examples: Mr. Darcy, Daisy Buchanan, Romeo/Juliet, Peeta Mellark, Edward Cullen, Mary Jane Watson

6. Confidant

This one’s even harder to pin down, especially since many stories focus so much on their MC’s love interest that other relationships get left out in the cold. However, the confidant can still be one of the most profound relationships the protagonist has in a novel.

Confidants are often best friends, but they may also be a potential love interest or even a mentor. The protagonist shares their thoughts and emotions with this person, even when they’re reluctant to share with anyone else. However, the confidant might also be someone the MC turns to, not because they want to, but because they feel they have no other choice (as in the last example on this list).

Confidant examples: Horatio, Friar Laurence, Alfred Pennyworth, Mrs Lovett, Jacob Black, Dumbledore, Hannibal Lecter

7. Foil character

A foil is someone whose personality and values fundamentally clash with the protagonist’s. This clash highlights the MC’s defining attributes, giving us a better picture of who they truly are.

Though these two often have an antagonistic relationship, the foil is not usually the primary antagonist. Sometimes the MC and their foil clash at first, but eventually see past their differences to become friends… or even more. (Think about the protagonists in When Harry Met Sally: first they’re foils, then friends, then finally lovers.)

The foil’s precise relationship to the protagonist depends on the differences between them. For example, if the MC is introverted, their foil might be super extroverted, but that wouldn’t necessarily preclude the two of them from becoming friends. However, if the MC is kind and selfless and their foil is extremely self-serving, they’re probably not going to get along.

Foil examples: Draco Malfoy, Effie Trinket, Lydia Bennet, George and Lennie, Kirk and Spock

Clearly foils. Just look at that color symbolism. Image: Lionsgate

Character Types by Quality

8. Dynamic/changing character

This one’s pretty self-explanatory: a dynamic character is one who changes over the course of story. They often evolve to become better or wiser, but sometimes they can devolve as well — many villains are made through a shift from good to evil, like Anakin Skywalker and Harvey Dent.

The protagonist of your story should always be dynamic, and most of the deuteragonists should be as well. However, you don’t need to make the changes super obvious in order for your audience to catch on. In the course of your narrative journey, these changes should come about subtly and naturally.

Dynamic examples: Elizabeth Bennet, Don Quixote, Ebenezer Scrooge, Neville Longbottom, Han Solo, Walter White

9. Static/unchanging character

Then on the other hand, there’s the static character — the one who doesn’t change. Many static characters are simply flat, and having too many is usually a symptom of lazy writing. However, certain kinds can serve a larger purpose in a story.

These static figures tend to be unlikable, such as Cinderella’s stepsisters and Harry Potter’s aunt and uncle — their ignorance to how they’re mistreating our hero makes them people we “love to hate,” and boosts our sympathy for the protagonist. They may also impart a lesson to the reader: you don’t want to end up like me.

Static examples: Mr Collins, Miss Havisham, Harry and Zinnia Wormwood (Matilda’s parents), Sherlock Holmes (a rare static protagonist), Karen Smith

10. Stock character

Stock characters aren’t necessarily flat either, though you do have to be careful with them. Similar to archetypes, stock characters are those familiar figures that appear in stories time after time: the chosen one, the joker, the mentor. You don’t want to overuse them, but they can really help round out your cast and make readers feel “at home” in your story.

The trick to using this type is to not just rely on their archetypal features. So when planning a character, you might start out with a stock, but you have to embellish and add other unique elements to give them depth.

Take Albus Dumbledore: he might seem like a pretty “stock” mentor in his wizened appearance and sage manner. However, his lighthearted wisecracks and weaknesses shown later in the series demonstrate that, while he may be based on a well-worn archetype, he’s a fully fledged character in his own right.

Stock examples (that are effectively embellished or spun): Scout Finch (the child), Nick Bottom (the fool), Haymitch Abernathy (the mentor)

Scout Finch — the archetypical child. Image: Universal Pictures

11. Symbolic character

As we mentioned earlier, a symbolic character is used to represent something larger and more important than themselves, which usually ties into the overall message of the book or series. This type must also be used sparingly — or at least subtly, so the reader doesn’t feel like the symbolism is too heavy-handed. As a result, the true nature of a symbolic character may only be fully understood at the very end of a story.

Symbolic examples: Aslan (symbolizes God/Jesus in The Chronicles of Narnia), Jonas (symbolizes hope in The Giver), Gregor Samsa (symbolizes the difficulty of change/being different in The Metamorphosis)

12. Round character

Don’t get this one confused with Humpty-Dumpty. A round character is very similar to a dynamic one, in that they both typically change throughout their character arc. The key difference is that we as readers can intuit that the round character is nuanced and contains multitudes even before any major change has occurred.

The round character has a full backstory (though not always revealed in the narrative), complex emotions, and realistic motivations for what they do. This doesn’t necessarily mean they’re a good person — indeed, many of the best round characters are deeply flawed. But you should still be interested and excited to follow their arc because you can never be quite sure where they’ll be led or how they’ll change. Needless to say, the vast majority of great protagonists are not only dynamic, but also round.

Round examples: Amy Dunne, Atticus Finch, Humbert Humbert, Randle McMurphy, Michael Corleone

No comments:

Post a Comment