Personalizing the Twelve Links of Dependent Origination

His Holiness the Dalai Lama often comments that as Buddhists, our distinctive practice is non-violence, and our distinctive view is dependent origination. His Holiness’s comments echo a common strand in the Buddhist tradition: Lama Tsongkhapa claimed that there was no teaching of the Buddha more profound than dependent origination, and Nagarjuna began most of his works by praising the “one who taught dependent origination.” The Buddha himself recounted that on the night of his enlightenment, he awoke to the profound nature of the twelve links of dependent origination, clearly seeing how beings trap themselves in an endless cycle of self-perpetuating confusion and misery.1 The Buddha went on to claim that nobody could understand his teaching without understanding the nature of these twelve links.2

Yet for many Dharma practitioners, these twelve links remain an elusive subject, something difficult to penetrate and even more difficult to relate to one’s personal experience and daily practice. Until several years ago, I was also apt to relegate this topic to the “too hard” pile. But after extensive study and debate with my classmates, and helpful elucidation of difficult points through discussions with Gen Losang Gyatso (“LoGyam”)—a senior monk in my house group, Lhopa Khangtsen,3 at Sera Je Monastic University in South India—I took the subject into retreat for personal contemplation. Although only able to generate some very limited, beginner level insights, I did manage to glimpse how profoundly relevant the twelve links of dependent origination must be for our own psychological situation. I will attempt to share some of my meager understanding in the hope that others will take an interest in studying and contemplating this important but dense subject.

Generally speaking, Buddhist texts that speak of “dependent origination” mean one of three distinct things: 1) dependence upon causes and conditions, 2) dependence on parts, and 3) dependence on a labeling consciousness. The second connotation is central to the philosophy of the Svatantrika-Madhyamaka School, and the third is unique to the Prasangika-Madhyamaka School. Thus, the “distinctively Buddhist” view—the one shared by all Buddhists historically and worldwide—is related to the first connotation, dependence on causes and conditions. This kind of dependence again has two divisions: a) outer cause and effect, and b) inner cause and effect. Outer cause and effect—the arising of smoke from fire, sprouts from seeds—is certainly not a unique Buddhist tenet, so it is inner cause and effect that is so central to Buddhism. Inner cause and effect, or psychological/karmic cause and effect, is the manner in which our present thoughts and actions create our future experience—that is, the twelve links of dependent origination.

This unique Buddhist view avoids the two extremes of 1) believing that some external force, such as a creator god, determines our experiences of happiness and suffering, or 2) believing that human joys and miseries have no deeper meaning, being the mere byproducts of the aggregation and interaction of particles, whose behavior is governed by outer cause and effect. Buddhism breaks away from most modern philosophies in asserting that these outer causes—the matter that interacts with but does not create our minds—are conditions for our experiences of pleasure and pain, but that the root cause lies deeper. All of us wish to have happiness and avoid suffering, and in many cases we have a sincere wish to free others from suffering as well. But as long as we remain ignorant of the true causes of suffering, even the most well-intentioned strokes to eliminate it can have only a limited effect.

What, then, is the cause of suffering? Anyone familiar with the Buddha’s first teaching on the four noble truths will recall that the Buddha insisted that delusions, karmic actions, and craving are the true origin of suffering. But how, exactly, do these three factors create suffering? The clarification of this subtle causal process is the subject of the teaching on the twelve links, a teaching that is simply an expansion of the first two noble truths.

The primary source for Mahayana teachings on the twelve links is the Salistamba, or Rice Seedlings Sutra [translation by author]:

Venerable Bhikshus, whoever sees dependent and relative origination, sees the Dharma.

Whoever sees the Dharma, sees the Buddha.4What is this dependent and relative origination of which I speak?

It is this: because this exists, that arises. Because this is born, that is born.

Whoever sees the Dharma, sees the Buddha.4What is this dependent and relative origination of which I speak?

It is this: because this exists, that arises. Because this is born, that is born.

It is like this: through the condition of ignorance, compounding factors. From the condition of compounding factors, consciousness … name and form … the six sense spheres … contact … feeling … craving … grasping … existence … birth … aging and death. From the condition of aging and death, agony, wailing, suffering, unhappiness, and mental disturbance all arise. Like that, merely this enormous heap of suffering arises.

The manner in which the twelve links function and interact is not clear in sutras such as the one quoted above, and so different interpretations have arisen over the course of Buddhist history. Some interpret the links as unfolding in a single instant, while others see them as representing stages of life. While I think all of these interpretations are beneficial for contemplation, for the sake of simplicity, I will follow the Gelug interpretation, formulated by Tsongkhapa in texts such as The Golden Garland, Lamrim Chenmo, and Ocean of Reasoning, based primarily upon Asanga’s exposition in Compendium of Manifest Knowledge and to a lesser extent on Vasubandhu’s Explanation of the Sutra on Dependent Relativity. Tsongkhapa’s heart disciple Gyaltsab Je further clarified Asanga’s presentation in his commentary on Compendium. As a Sera Je monk, I will of course rely in part on Jetsun Chökyi Gyaltsen’s textbooks.5

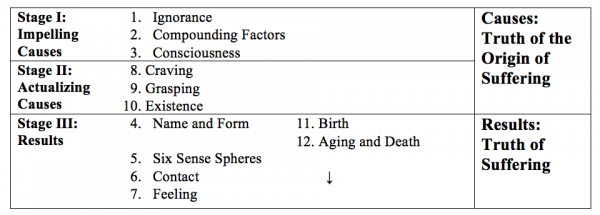

According to Asanga, the progression of the first to the twelfth link, as described in the sutra above, is meant to give a general picture of cause and effect (I will explain how later on), but does not actually illustrate how the process unfolds for a particular action creating a particular result. Instead, a complete cycle of the twelve links unfolds as follows:

Ignorance (1) leads to compounding factors (strong karmic actions) (2), which make an imprint on consciousness (3). Then, craving (8) and grasping (9) ripen that imprint, which then resurfaces in conscious awareness at the time of death as existence (10). The substantial continuum of that mind becomes the first moment of the next rebirth, which is both name and form (4) and birth (11)—these two are simultaneous. From the second moment of that new birth, aging and death (12) begin. During subsequent stages of fetal development, six sense-spheres (5), contact (6), and feeling arise (7), consecutively, and aging and death continue.

Thus, (1), (2), (3), (8), (9), and (10) are the causes, and (4), (5), (6), (7), (11), and (12) are the results. Specifically, (1), (2), and (3) are the impelling causes that leave an imprint on the mind, and (8), (9), and (10) are the actualizing causes that ripen that imprint and lead to a new suffering rebirth. Although this process can appear confusing at first, through habituation we can start to see the logic involved. Also, the non-linear progression highlights that these are twelve links of interdependent origination: although it is possible to trace a particular pattern of cause and effect, all the links should be understood to be mutually reinforcing and interpenetrating. Ignorance causes karmic action, but the imprints of karmic action lead to more ignorance. In a single progression, craving leads eventually to feeling, but feeling itself becomes the main cause for more craving in the future (more on that later). The conceptual structure gives us a microscope to pick out patterns in our own psychology and make sense of what often can seem to be a chaotic, non-linear process.

All twelve of these links are instances of samsara, which is no more than our own body and mind, and the uncontrolled cycles these go through in this life and future lives. Samsara is not a place we cycle through, but the cycle of moving through these twelve links. As the great Indian scholar Kamalashila explained in his Commentary to the Rice Seedling Sutra, “For those confused regarding the process of entering into and reversing samsara, and so that they may be free … the Buddha explained dependent origination.”6 Keeping in mind the general order laid out above, let us now look in more detail at each of the twelve links.

Stage I: Impelling Causes (Links 1, 2, and 3)

1. Ignorance

Generally, any mind that is confused in regards to the object it apprehends is accompanied by the mental factor of “ignorance.” For example, when we see double, the eye consciousness is mixed with ignorance, and when we wrongly believe that somebody’s friendly advice was meant as a criticism, ignorance is involved. Buddhist practice ultimately seeks to free us of all manifestations of ignorance, but with limited time and energy, we need to identify the most important ignorance that is leading us repeatedly to cause suffering to ourselves and others. Even regarding this “first-stage ignorance,” different Buddhist scholars identify it slightly differently: for Asanga, it is like the darkness that leads to misperception, thereby not being a wrong apprehension but rather a lack of apprehension. Dharmakirti insists instead that it is a very specific wrong apprehension, namely the view that there is a substantial, self-sufficient “me” that exists over and above the aggregates of body and mind, similar to there being some kind of substantial entity called “New York” that exists over and above the buildings and people. Chandrakirti adds that it is not only this view of self, but the view of all phenomena possessing some intrinsic, findable nature in this way. The Theravada tradition takes a practical approach, identifying “first-stage ignorance” as misapprehension of the four noble truths: any view of reality that does not recognize craving as the cause of suffering will lead to actions that perpetuate suffering.7 How can we make sense of these various presentations?

Although these authors choose to focus on one particular cause, all of them would agree that all of these causes are involved. We cannot isolate one mistake and toss it out; we have to recognize a vast and deeply entrenched network of misapprehensions that entangles our minds. When a government is riddled with corruption, the result will be ineffective governance and harmful foreign policies. But a campaign to end corruption cannot just fire one person and be done with it. We have to identify and meditate upon all the ways we misrepresent reality: we expect youthful bodies to stay fit and healthy forever, see toxic substances and relationships as sources of stable happiness, and relate to the environment that sustains us as a stockpile for consumption.

2. Compounding Factors (Strong Karmic Action)

Misconceptions naturally lead to poorly planned actions. Every action we do under the power of ignorance is a karmic formation, but some are naturally stronger than others. Those with enough force to impel a new rebirth are called impelling karmas, and that term is synonymous with compounding factors, the second link. Pabongka Rinpoche explains in Liberation in the Palm of Your Hand that these are usually actions of body and speech—mere mental intentions rarely have the same level of force, though in certain cases they can.8 A good example of a negative karmic formation is killing somebody under the power of anger. A positive one would be taking a vow to refrain from killing. Until we directly perceive emptiness in meditative absorption, even our most positive actions will to some extent be tainted by wrong conceptions about the self, and thus will lead to rebirth in samsara, albeit a positive one. Each single action is a single impelling karma—two actions do not combine to create one life, though a second action may condition particulars about that life. I asked Gen LoGyam how this provision would work in regard to taking monastic vows—after all, isn’t this something that I perform over time, rather than just a “single action”? He explained that every time a practitioner remembers his or her intention not to harm others or follow attachment, that aspiration is itself a strong imprint that could impel an entire lifetime—so we may create many such imprints each day. Because the intention is to refrain from bodily harm, it becomes an action of body, thus according with Pabongka Rinpoche’s qualification.

The Tibetan word for “impel”—“phen”—can also mean “to throw” or “to shoot” an arrow. Asanga explains that each karma we create is like shooting an arrow straight up into the air. At some point in the future, it will strike down upon the bowman. Remembering that we have countless arrows hovering in the sky in wait for an opportunity to dive is a strong impetus to work out our past karma and limit its further creation.

3. Consciousness

Many years ago when I first read about the twelve links, I was confused as to how consciousness could be the result of karmic formation and ignorance. Is Buddhism claiming that there is no consciousness before that time? Isn’t ignorance itself a kind of consciousness? What I didn’t understand is that “consciousness” here does not refer to consciousness in a general sense, which itself is primordial, existing without beginning, just like matter and space. Rather “consciousness” refers here to a particular instance of consciousness that carries the imprints of karmic actions. Specifically, it is the substantial continuation of the very consciousness that created a karmic action. Gen LoGyam explained, “Imagine if you became furiously angry and killed another person. After completing the action, that anger and aggression would still be manifest in your system. That moment is the third link. After some time—maybe a few minutes or hours, maybe even a day—that energy would calm down, but would not disappear. Instead, it would become dormant in the recesses of your mind as you move on to other thoughts and activities. You may even forget about it, but it would not disappear.”

To understand the concept of “dormant mind,” think of some skill you have developed, perhaps driving a car. Although the knowledge of how to drive a car is strongly imprinted in your mind, you don’t have to consciously think about it twenty-four hours a day. But even if you don’t drive for ten years, when you again sit behind the wheel, that knowledge will become manifest again with little conscious effort. According to Buddhist philosophy, we have many—practically infinite—dormant mental states that reside in a non-manifest manner below our conscious awareness, and wait for a suitable trigger to cycle back up to the surface. Actions done with strong emotion and/or habituation leave strong imprints. These imprints wait for suitable conditions to ripen them and then impinge on our experience.

Stage II: Actualizing Causes (Links 8, 9, and 10)

8. Craving

Although ignorance is the root of cyclic existence, craving is the strong and direct cause that fuels the process. We all want to be happy and avoid suffering, and craving is the natural expression of that dual wish. Twenty-four hours a day—even in dreams—a continuous stream of thoughts and feelings bubbles into our consciousness. These thoughts and feelings fall into link 7, as I will discuss later. The process is normally too subtle for us to recognize, but the thoughts and feelings that arise are imprints of past thoughts and feelings, lying dormant in the mind through the process outlined above in links 2 and 3. Failing to recognize these experiences as being the manifestation of our own mind, we imagine the causes to be present in our immediate circumstances, when in actuality these circumstances are only the trigger for a deeper inner process. At a preconscious level, we constantly engage in habitual thinking that projects qualities onto external objects, labeling them as the cause of happiness or the cause of suffering. We then wish to obtain or hold onto those objects that seem to cause pleasure and separate from or destroy those that seem to cause pain. As such, it is not wanting pleasure and wanting to avoid pain that is in itself the problem, but rather the wrong thoughts that exaggerate the qualities of objects. However, manipulated by ignorance in this way, desire becomes a misguided force, and takes us for ride after ride.

While feeling (7) is like an itch that we can’t even identify, much less scratch, craving is the constant thought that responds to that feeling, thinking, “I’d like to have this, go there, do that.” Not realizing that we are trying to escape a feeling in our own mind, we compulsively engage in new actions, expecting the outer experience to satisfy us. But by the time we get where we intend to go, we have already moved on to thinking about something else, and fail to recognize that the original itch did not disappear but has merely been replaced by another “itch,” the imprint of another past action.

Craving is of three kinds:

1) Craving for pleasure. This is a response to a pleasant sensation, wishing to repeat or prolong that sensation. For example, we may recall eating a particular flavor of ice cream and wish to repeat that experience.

2) Craving for annihilation. This is not a suicidal thought, but rather a thought that responds to a suffering sensation by wishing to avoid it or destroy it. We may recall a bad experience and try to distract ourselves in something enjoyable.

3) Craving for existence. This is a response to the neutral, peaceful sensation of deep meditative concentration, wishing to abide in that sensation perpetually. Gyalwa Gendun Drup, the First Dalai Lama, explains that this is called “craving for existence” in order to dispel the view that the higher realms of meditative absorption are true liberation—they are still within samsaric existence.9

Like scratching an itch, all of these responses only serve to intensify the inner feeling and strengthen the force of past imprints, leading us to engage again in strong karmic actions (2) and thereby thicken ignorance. Tsongkhapa explains in the Lamrim Chenmo that without ignorance, there would be no craving response even if feeling (7) did arise.10 Again we can see how links 1 and 8 mutually reinforce one another.

When feelings arise, the best response would be to carefully observe the nature of the mind and how it responds to those feelings. Habituation to craving makes that simple response extremely difficult, and without realizing, we engage in one action after another, a pattern that will naturally continue at death if we do not retrain the mind.

The First Dalai Lama provides a strong warning about the dangers of craving:

It sweeps us into the torrent of existence, so difficult to cross

And spurred on by violent karmic winds

It churns with the great waves of birth, old age, sickness, and death.

Save me from the terrifying river of desire!

And spurred on by violent karmic winds

It churns with the great waves of birth, old age, sickness, and death.

Save me from the terrifying river of desire!

9. Grasping

The ninth link is merely an intensification of the eighth link, craving, at the time of death. When it becomes apparent that the things that we relied on to support our sense of self—family and friends, wealth and possessions, even our body—will no longer support us, we are left with the feelings with which we have struggled for so long. If our habitual reaction has been to cling to pleasurable feelings and try to avoid uncomfortable ones, that reaction will naturally continue here.

Left with only the inner feeling, this intensified craving response will trigger the ripening of a dormant experience.

10. Existence

The name “existence” here means “samsaric existence” and is a case of the name of the result being given to the cause. This is the last moment of gross consciousness in a lifetime, and becomes the substantial cause for the first moment of consciousness in the next samsaric life. Rather than passing into nirvana, we continue in samsaric existence, so the last experience of our life is called “continued existence” rather than “the end.”

Existence (10) is synonymous with actualizing karma, and is actually the substantial continuity of the impelling karma, link 2, that became link 3 and then passed into dormancy. Remember how Gen LoGyam said this strong mental energy would never disappear? At this point, it reemerges in conscious awareness. Gen went so far to say that if we killed a particular person, the memory of that action, and of that person’s face, will flood our consciousness at the time of death, as though we are reliving the experience. That anger and aggression will then be the powerful imprint that carries us into the next life and conditions our future experiences.

Of course, we may not have created such a heavy imprint in this life, and in that case, an imprint from a karmic action in a past life may also arise. What is certain is that only one imprint will arise—other strong imprints may act as supports, but one particular one will be dominant and become the actualizing karma that directly leads to the next life, like an arrow falling from the sky that has met its mark.

As sense experience fades away, this strong final experience gets “locked in” as our last conscious thought in this life. After that, the mind enters into a subtle, neutral state, and unless a practitioner has actualized the completion stage of highest yoga tantra, he or she will be unable to engage in further practices.

Stage III: Results

4. Name and Form and 11. Birth

Although these two links are listed separately, in the process of a single round of cause and effect, they both occur simultaneously, at the moment of conception in a new life. “Name and form” refer to the mind and body, the aggregates that make up a person. The use of this terminology predates the Buddha, who simply adopted it. Mind is given the label “name” because it engages objects through the force of discriminating “this is this, that is that.”11 “Birth” is not birth from the womb but conception, which for Buddhism is the first moment of a new life. The mind carried into this birth is a continuation of the mind that became dormant at link 3 and manifested again at link 10. Already at conception, our mind, body, and even our environment are charged with the contaminated energy imprinted by our past actions. As Asanga explains in Compendium, “what is the truth of suffering? Know it as the beings who are born, and the world into which they are born.”12

12. Aging and Death

Aging does not simply mean getting gray hair and wrinkles, but refers to the process of constant change that begins at the very moment of conception. Thus, this link begins right away. But because death can occur at any time, even before manifest aging sets in, these two stages are grouped together.

5. Six Sense Spheres and 6. Contact

Name and form (4) lasts until the fetus begins to develop sense organs, at which time link 5 begins. When the sense organs begin to function, and there is the contact of objects, sense organs, and sense consciousness, link 6 begins. We can see the emphasis placed here on the development of conditions that will lead to creating karma once again. We can also see that in this system, a baby in the womb is not a “blank slate,” but is already completing a process that has been set in motion by mistaken views and habitual craving.

7. Feeling

At contact (6), a baby in the womb could already experience feelings of pleasure and pain, but had not yet begun to distinguish certain external objects as the cause of pleasure and pain. When inner thoughts—habituated by karmic imprints from the past existence—reawaken to that process, we enter feeling (7), which lasts until death (unless somebody’s mental faculties deteriorate such that again they cannot distinguish the causes of pleasure and pain). At this point, a person begins to react habitually to feeling with the three kinds of craving—conditioned by ignorance—and again create strong karmic actions. The previous cycle has completed, and a new one begins.

After describing the twelve links individually, the Rice Seedling Sutra continues:

From the condition of aging and death, agony, wailing, suffering, unhappiness, and mental disturbance all arise. Like that, merely this enormous heap of suffering arises.

The teaching of the twelve links does not end with aging and death, but continues on with agony (bodily suffering), wailing (verbal suffering), and three forms of mental suffering. The purpose of this last section is to illustrate the normal progression that life takes, such that we may develop a wish to be free of this uncontrolled process of rebirth. The phrase “merely this enormous heap of suffering” indicates that the process does not involve a substantial self, but is a natural process of cause and effect. The reason this last result is not counted as a thirteenth link is that it does not necessarily follow as a result of aging and death: a pure Dharma practitioner can die peacefully and without regrets.

The question remains: why, if the causal order moves from steps 1-3, then 8-9, then 4-7, did the Buddha originally teach it in the order he did? I believe he did so in order to illustrate the crucial causal nexus of links 7 and 8, feeling and craving. Although in a single set of cause and effect, craving comes first, the feelings we currently experience as the result of countless past cycles are the main cause for the craving that will cause a new cycle. And disentangling this set of cause and effect is decisive in understanding how we create our own suffering. Within the foundational Buddhist practice of the four close placements of mindfulness, the second, mindfulness of feelings, is specifically a means of recognizing the truth of the origin of suffering by closely observing the way feeling fuels the craving that creates future suffering.

Among the five aggregates that constitute a person—form, feeling, discrimination, compounding factors, and consciousness—the first is the body, the last is the main minds, and the fourth includes all mental factors other than feeling and perception. Why, then, are these two singled out? Gen LoGyam explains that it is because they are the two most important in creating samsara. Our attachment to pleasurable feelings, and aversion to unpleasant ones, is the motivating factor in all karmic actions. Discrimination includes our beliefs about the nature of reality, and these determine which actions we believe will maximize pleasure and minimize pain.

Although feeling here includes both sensual and mental sensations, I think that for human beings, subtle mental sensations beyond conscious awareness are often the primary motivating factor in our actions. We are intensely social animals, and relatively few of our actions are directly related to achieving sensual gratification. Much more of our mental energy is focused on how we might like others to perceive us, or spending time with people or in places that we enjoy. As such, what we consider worth pursuing is constructed more by subtle concepts than by biological instinct. So, the feelings most relevant to what we crave are likewise subtle ones. Usually we aren’t even fully aware of our own motivation for actions. A preliminary step towards identifying the relation between this seventh link of feeling, and the eighth of craving, is to slow down and develop sufficient concentration to observe this subtle interplay.

As we first learn to meditate, the uprush of unprocessed feelings can seem like a clogged pipe. But with patience we can learn to identify individual sensations, and may even be able to trace their origin to specific events in our past that have remained unresolved in subliminal levels of the mind. In doing so, we begin to recognize the power of karmic imprints to remain and later influence behavior and experience, and we can apply skillful methods to disarm these dormant—but not inert—imprints, which left unattended can eventually ripen strongly enough to impel entire uncontrolled rebirths. Highly advanced practitioners with superb concentration will eventually move beyond the present lifetime, and trace the progression of cause and effect over multiple lives, much like the Buddha did on the night of his enlightenment. But until we are able to do so, we can contemplate the teaching on the twelve links and begin to gain an intellectual understanding of the process.

Such an understanding itself leaves a strong imprint to eventually gain direct experience and, ultimately, liberation from the process altogether. Even if we cannot gain such profound insight right away, we can learn to be careful of our actions by being watchful of our motivation, paying especially close attention to the way that habitual, unskillful responses to feeling lead to craving and then to unskillful, ultimately self-destructive actions. We can also rejoice in knowing the positive results we can create simply by choosing to abstain from habitual impulses.

What is more amazing than this,

And what is more excellent than this?

By praising you in this way,

It becomes a praise! Otherwise not.

And what is more excellent than this?

By praising you in this way,

It becomes a praise! Otherwise not.

-Tsongkhapa, Praise to the Buddha for His Teaching of Dependent Origination

Ven. Tenzin Gache (Brian Roiter) is an American monk living at Sera International Mahayana Institute (IMI) House in Bylakuppe, India, and studying at Sera Je Monastic University.

Feature image: Hub portion of Wheel of Life, Khachoe Ghakyil Ling, Kathmandu, N

No comments:

Post a Comment